When we are compelled to bid farewell to a loved one, we understand that we, with varying intensities, will feel pain over that loss. We speak of closure, of grief in stages. To the hurting soul, we give tender hugs and promises that time will bring with it a salve for their aching heart. For some, that alleviation of pain over a loss comes smoothly. For others where the attachment was more deeply grafted into their lives, it maybe doesn’t fade as quickly. Everyone grieves differently. At some point, though, we have set for ourselves an expectation of eventual healing. We learn to honor those who’ve gone on, to smile at the memories, and to keep living.

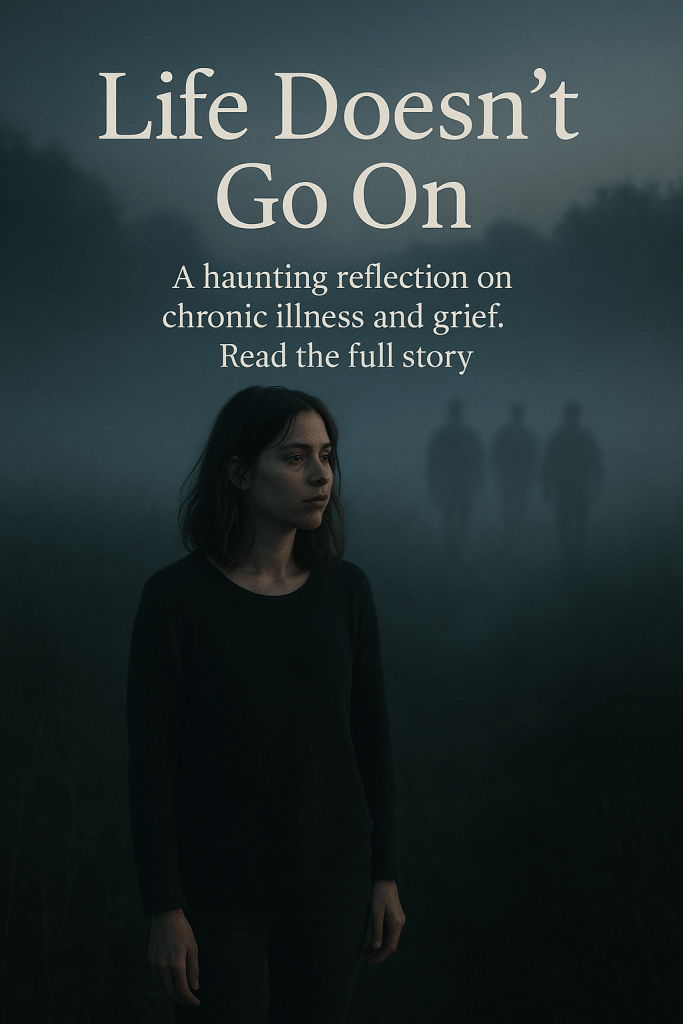

But imagine if our adored deceased didn’t allow us to heal that heartache? What if they occasionally reemerged into our lives, to walk about just beyond our touch, their visual taunting us with a new hope, only to shuffle off this mortal coil once more? We could never completely obtain closure.

For a person diagnosed with a degenerative disease, this is a common reality. The initial diagnosis is the first loss. We are numb. It feels as if we’ve been given someone else’s news. This can’t be our life. Determined that modern medicine is mistaken, we decide that we’re going to keep on living and not allow this perceived monster to affect our plans. We accept the change – with an asterisk beside the word accept. The change is real, but only on paper. We’ll be fine. Then, one day, perhaps it’s a small symptom, like a wave of vertigo. Or, maybe it’s a massive, sudden progression that leaves us seeing double until a treatment can alleviate. Either is cause for our deeply cradled denial to ponder it’s influence . We become frustrated over forfeited physical functions, then angry. Angry that our plans may be paused, that our promises hold no permanence.

After a bit of an internal (or maybe very real external) tantrum, we rally. This thing is here to stay, but it can’t destroy us. We’ll let it exist – we simply need to be more careful. We alter our daily routines just enough to allow us extra rest, and we become acutely aware of when we’ll have to hide a tremor by claiming we need an “office day”.

We are successful in our willingness to work within our barriers. Often our assumed agreement with this autoimmune dictator holds up for years, allowing us a belief that we really are in control.

Until it doesn’t. One day out of nowhere, it sends in it’s hosts, slamming into us with a fervor. Something in our life is forcefully cancelled – could be a long awaited social event, or maybe a promotion we’ve worked tireless hours for. The reality of our decaying future plans settles in and we spiral. Depression surrounds us like a weighted blanket, allowing us just enough air to continue breathing. We stay in that heavy, false comfort as long as we can bear the weight of our grief, not ready to test what we can still become.

Finally, like a gothic caterpillar, we emerge from our cocoon. We’ve evolved into someone different, something different. Still beautiful, still able to fly, but we are darker, somehow tragically alive. We’ve accepted our perceived life of death. Our humor becomes tinged with a black cynicism. We are what we are.

And so it begins. We discover a dedicated doctor and a promising treatment. Our quality of life improves. For a time, we brighten and lighten our step. Hopes of recovering archived dreams emerge, and we’re excited about possibilities.

Then they come. The score of redundant relapses, each pillaging us of some valued ability.

Soon we are simply existing in a volatile cycle of symptoms and grief steps. Those reappearing dreams fade into ethereal visions, because each time hope fades again, something of their existence becomes less distinct. We know they’re not real. Still, we see them again, and again, with each new treatment, through each translucent hope.

Life doesn’t go on.